Martina Muck

Zeichnungen

Zeichnungen

New Modern Fuel Show Makes the Mundane Sacred

May 20, 2014 | by Kelly Reid

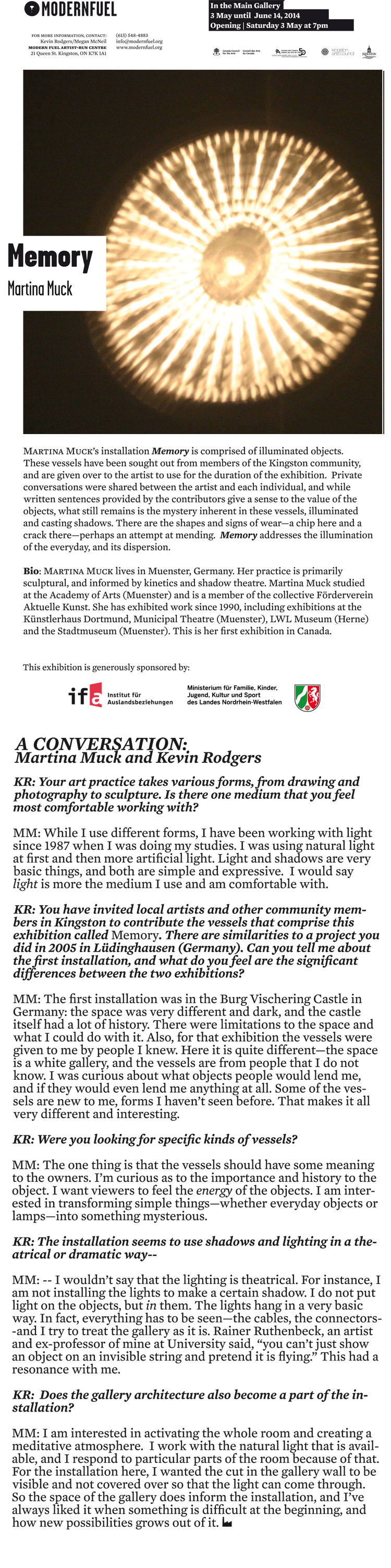

One of the final shows being held at Modern Fuel’s current space before later this summer is Martina Muck’s installation Memory. It’s a beautiful show, highlighting—quite literally—the innate sacredness of everyday objects. The show consists of twenty-two vessels that range from near garbage (a plastic spoon found near Lake Ontario) to childhood treasures (a first guitar case). Each piece sits on the floor, alone, and illuminated by a single dropped light. The effect is striking when you walk into Modern Fuel’s intimate space. The vessels are like so many candles on an altar; and indeed, Muck seems to be worshipping these objects in some way.

They actually don’t belong to Muck at all, but were collected from members of the Kingston community. For each piece, Muck had a conversation with the donor about its significance. On one of the walls, on small, inconspicuous white cards, a single sentence explains each object. A bird’s nest both fragile and strong; a souvenir from Sarajevo; a cup bought at a garage sale in 1995; a Russian jewelry case that has been passed down for three generations; an old box that used to hold rubber bands and stamps; a bowl that represents years of bad marriage, and sixteen other vessels both mundane and exquisite. The guitar case is by far the largest; most are small cups and bowls. The smallness of each piece requires the viewer to have a keen eye for detail and an appreciation for minutiae—both good things. Each object is lent to the installation for its entire duration, which is a lovely exercise in trust as well.

Muck, a German-born artist, often plays with light and shadow in her work, and this installation is no exception. Each vessel sits alone, spaced well apart. The lights from above, though, make the shadows swell and overlap with one another. Nothing exists in and of itself, the show seems to say. Objects cast metaphorical shadows with their history, stories, owners, and futures. These disparate objects are connected now, and forever. The light, then—that small measure of seeming worship—is so appropriate. Even a simple bird’s nest is sacred. This is definitely a show to take a look at. It’s likely one of the loveliest displays you’ll see all summer.

This is Muck’s first show in Canada, and it will run at Modern Fuel until June 14.

See more at: http://www.kingstonist.com/2014/05/20/martina-muck-memory-

MARTINA MUCK,

Memory

, Modern Fuel (Kingston, Ontario), May 3 - June 14, 2014

Memory, mounted at Kingston’s Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre in May and June, was the first Canadian exhibition for artist Martina Muck, who lives and works in Munster, Germany. Modern Fuel’s initial online Call to Participate stated: Please join us in welcoming visiting artist Martina Muck (Germany) to Kingston...The artist is seeking vessels of varying types (and learning about the stories that accompany them) to use as part of the evocative exhibition, where each will be displayed under different forms of illumination.

The vessels soon began arriving at the gallery—along with notes outlining the special meanings they bore for each contributor. By the time the exhibition opened on May 3, there were about twenty-five wildly varying kinds of vessels on hand, which Muck had deftly arranged on the gallery floor, each one now illuminated by small but powerful mini-floodlights suspended directly over them, hovering close to them, flooding them with a personal radiation strong enough almost to dematerialize each one.

The vessels, which ranged from a ladle to a vase to a bird’s nest to an open, scarlet-lined guitar case, were now bound into relation, not only by their having become part of an aggregation of objects gathered into one exhibition space, but because their all being similarly illuminated had optically valourized each one—regardless of how banal, inelegant, kitschy or generally unappetizing each one actually was. One touch of floodlight apparently serves to make the whole world kin.

As far as I could tell, individual differences in the vessels—except perhaps for the morphological power of the furnace-red guitar case and the fragile, relic-like vulnerability of the little bird’s nest—were softened, melted, into a new role whereby each object gave up much of its specificity to become talismanic. The equalizing light lent every object continuity with every other object, each one of them now sharing the theatrical status of the others. If these vessels were, in fact, to be the bearers of the personal memories of their donors, then these memories were now in distinct danger of being lost in the continuum of the vessel-adjacent-to-vessel-adjacent-to-vessel arrangement.

Muck’s borrowed vessels were now like actors (under stage lighting), delivering lines about the memories they were expected to embody—but at one remove from those memories themselves.

I would suggest, therefore, that the memories summarized by the title of Martina Muck’s exhibition, Memory, are, in fact, only displaced and deferred memories, frayed, strained and altered. They are memories that may have been vivid while they lived in and tinctured the various objects making up the exhibition, but, in the end, were now utterly transformed into the idea of memories.

This serves nicely, of course, to deliver Muck’s installation from the sentimentality that would assuredly have befallen it if each of her gathered vessels were still being used as the loci of memory, as (to borrow and distort Andre Breton’s phrase), Communicating Vessels. As it is, all the vessels really communicate is their own floodlit morphology—their formal qualities, heightened and enhanced by the falling of light upon them.

On one wall of the gallery—at a substantial remove from the floor-installation itself—there were affixed a number of white cards on which were printed, in black type, the vessel-donor’s remarks about his/her contribution to the installation. The notices varied enormously—not surprisingly—in the degree to which they were affecting, informative, amusing or even off- putting.

Some were touching: This is a chest that my Omi brought from Germany. I like it because it looks like a treasure box that has been all over the world. Some were charming but inexplicable: This gorgeous little plate serves well, its value keeps growing [what is meant by serves well? That the plate is useful to serve things on, or that it serves its purpose well as a plate—a broader, more general meaning?]. Some were irritatingly clever to the point of being gnomic: On Kidd Road we reap what we sow. Some were disturbing: This bowl represents 38 years in a painful marriage [38 years of a painful marriage, surely?].

And a couple sidled up to real poetry: I discovered this nest on the ground, during a walk in the forest. A bird’s nest is both fragile and strong. I go into the forest often feeling fragile but come out strong.

The wall of messages and annotations was, then, aquiver with emotion—with tenderness, nostalgia, resentment, anger, a sense of fulfilment, a sense of loss.

But all of these feelings—preserved on these cards with varying degrees of fidelity to the emotions that originally engendered them—were now profoundly separated from the vessels to which they had formerly been attached.

For me, Martina Muck’s handsome, affecting installation was not, therefore, about memory at all but rather about

Gary Michael Dault in der kanadischen Kunstzeitung Vie des Arts 3/2014

Martina Muck Interactive Sculpture at Artweek 2009, Aabenraa, Denmark

During Artweek, Martina Muck creates a growing sculpture that extends from and along a flagpole in the harbour district. The artist has placed a notice about it in town and she gets in touch with passers-by in order to get them to bring her things to add to the sculpture. This way, her work grows by the day, changing character as new objects are added while other objects must be changed in order to re-establish the balance and the aesthetic of the sculpture.

Can you explain a bit about the concept you’re working with here?

During a few of my earlier projects, I worked with the things that other people gave to me. I used to work only for myself without letting anything from the outside influence my work, but now I’ve changed the way I work. I did so because I think, it is an interesting aspect, to work with a material that I don’t know beforehand but which has meant something to someone else. I like how other people’s feelings and soul get in touch with my works in this manner, which is the reason why I became interested in this project because it had to be communicative. It’s the first time that I’m working on a project this open – usually I’d ask people to bring specific types of objects, but in this case, anyone can decide for him- or herself what to donate to the project.

Incorporating any type of object – a surf board, a double-bass, or a piece of a garden fence – into a work of art and actually making it work is not an easy task. This project is a challenge for me because I have no way of predicting the outcome. The result is unknown but the process is a very good and important part of the project.

What do these everyday elements mean to you?

A lamp, a table, or a chair is a basic object that everyone has, and when you have these things, you can perform most of your everyday tasks. They sort of represent signs that everyone understands the meaning of, involving everyone. That is the reason why they can potentially get people emotionally involved and therefore I prefer to work with those kinds of things.

Do you use everything you get?

Yes, I try to. Yesterday, however, I received a swede which I first intended to use, but later I decided not to. I don’t want my work to change in a way that some parts of it eventually will rot. But apart from that, I’ll use everything as long as I have enough time to incorporate it into the art work.

Are there any objects you like better than others?

I like the chair a lot and the simple, constructive things. Also, the things that have been given with the heart, like the double-bass.

The finished work will be a large, sculptural installation, stretching with dynamic structures into the surrounding space, resembling a giant abstract drawing. All the objects given to the artist will respectfully be steered away from their original uses and given new meaning in context with the art work. This way, the heart of the piece is the old double-bass that has been owned by one family for many years and thus has great sentimental value to the people who donated it to the project. Combined with a torn bed sheet, a cone-shaped metal net for floral decorations becomes a princess hat with streaming ribbons, and a bag of beach finds transforms into a picture when placed in a box and wrapped in cling film.

The artist stresses the importance of treating the material respectfully. It would be wrong to smash something to pieces when the object has meant something to whoever donated it.

This piece of art possesses some interesting aspects for the citizens of Aabenraa because for those who gave some of their things away, it is exciting to see how they become a part of an art work, and the work becomes interactive by drawing the citizens into the creative process. However, despite the fact that the thought about turning your everyday objects into art and even creating a discussion about our consumer culture seems perfectly harmless, this very piece of art has been the most disputed work of Artweek.

It is important to notice, though, that while some old and used objects may seem like trash to some, they may be valuable treasures to others. The aesthetic of the sculpture may even make us consider what we choose to give to others throughout our lives, literally as well as figuratively.

Author: Sofie Pil Eriksen.

Taken from the Aabenraa Artweek 2009 catalogue